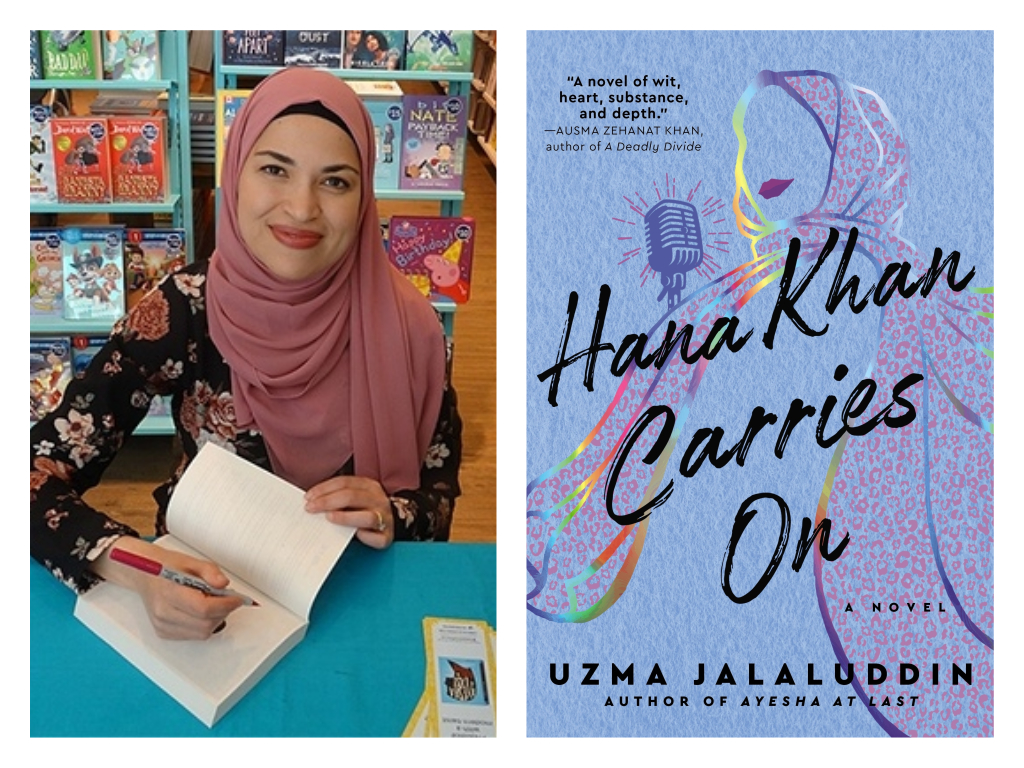

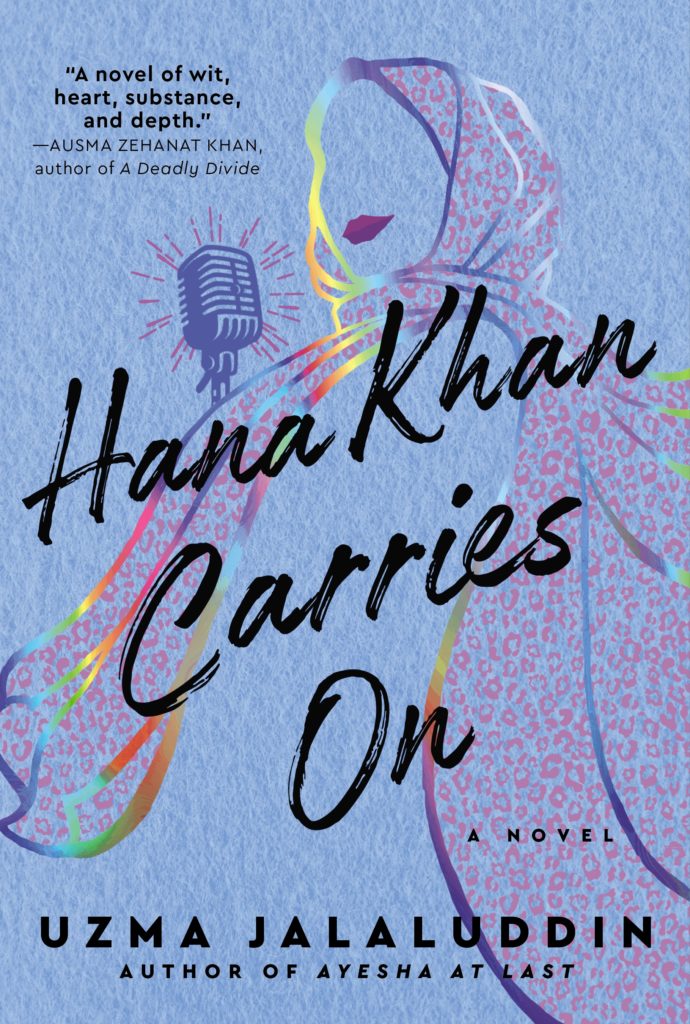

Uzma Jalaluddin is the author of Ayesha at Last and Hana Khan Carries On. A high school English teacher, she is also a Toronto Star columnist and a contributor to the Atlantic. Her first novel was published in the US, the UK, Australia and India and was optioned for film. Hana Khan Carries On has been optioned for film by Mindy Kaling.

Uzma Jalaluddin chats with ANOKHI LIFE’s Editor-In-Chief, Hina P. Ansari

Hina P. Ansari: Welcome to The ANOKHI Uncensored Show, I’m your host, Hina, and I’m thrilled to have Uzma Jalaluddin, the author of Hana Khan Carries On as my special guest. Thank you so much for joining me today.

Uzma Jalaluddin: Well, thank you so much. I’m really happy to be here.

HPA: For those of you who do watch and listen to this show, you probably recognize her name because I had her on earlier this year, actually when your book came out. So this time around, I wanted you to be a part of our The ANOKHI Advocate List and this is to commemorate our 19th anniversary of a ANOKHI. So again, thank you for being a part of this. I’m really excited to get your perspective on what we’re going to talk about the whole idea of advocacy in literature.

UJ: Yeah, sounds good.

HPA: So like I said, first off, when we were together before your book Hana Khan Carries On came out, since then, you’ve had quite a lot of pretty amazing developments. One of them most notably, Mindy Kaling who optioned your book to make it into a film. So tell me a bit about your reaction to that and where are you now in that process?

UJ: Yeah, I’m really excited. And actually, when we spoke, I knew that my book had been optioned. To give you and your listeners a little bit of context [on how] IP projects [intellectual property] are sort of optioned these days. Oftentimes, it happens very, very early on. So Hana Khan Carries On is a book that I wrote. I own the IP for it, and shortly after I had submitted the book to my editor with the final edits, I also gave it to my film agent, and his job is to shop around and see if there would be any interest from any producers willing to turn it into a movie or television show miniseries, whatever the case may be. There’s a big market for for this type of thing, and we figured there would be some interest because my first novel was also optioned. That was optioned by Pascal Pictures way back in 2018. So this was the hardest secret to keep. My book came out in April 2021 but it was optioned way back in October, November 2020. And I just had to be quiet about it until almost ten months later when the news came was finally officially announced in August 2020. Not even when the book launched. And I just I was sitting on this amazing news and I couldn’t tell anyone. So I’m very good at keeping secrets. (laughs)

HPA: I’m excited to hear about it, Good to know you are very good because when we had our interview, you were great, but that must have been bubbling inside of you just because it’s such good news.

UJ: It was. And to your question, I was thrilled. I mean, I think I was walking around in a daze for a couple of days because Mindy Kaling is such an icon. She is such an inspiration to me personally. I’m also a huge fan of hers. I’ve been watching her kind of develop and grow as an artist and now is this badass producer. She’s running a very successful company, and I love everything that she does. I really feel like, strangely, I guess our tastes sort of aligned, and we did end up having a Zoom meeting where I met her virtually, which was fantastic. She’s lovely. And she said that You’ve Got Mail, the original iteration of the movie that my novel is based on, is her favorite movie. It’s one of her favorite rom-com movies of all time. So this was written in the stars, it was meant to be. I obviously didn’t know that when I was writing my book way back in 2017, but I’m beyond thrilled!

HPA: Oh, that’s so exciting. So everyone, please keep an eye out for Mindy Kaling’s film, which is based on Uzma’s book Hana Khan Carries On. Do you know when it’s coming out? Do you have that info yet or no?

UJ: It’s a very long process. It will take years, things get optioned and the very first step is — they’ve actually done the first step — they have hired a screenwriter and she’ll be working on that process and that could take, you know, a year or even longer. So it’s exciting, but you know, don’t hold your breath. It’ll take a while.

HPA: We’ll be keeping an eye out for that. The reason why we brought you on the show was to talk about representation in literature. And that brings me to today’s show talking about advocacy. So my first question for you is, what does advocacy mean to you?

UJ: I always somehow associate it with the political realm, and I know I shouldn’t, because even my other job is (I’m a high school teacher) and we always tell our students, you know, it’s really important for you to advocate for yourself to make sure that you speak up. Speak out if you need any accommodations or if something is bothering you and things like that. And yet somehow, I still associate it with a very political process. And yet, as I have sort of joined this artistic life, and I’ve delved more deeply into my own artistic aspirations, I realize that advocacy can take so many different forms, even with the stories that I write. Simply by writing a book about Muslims with a mostly Muslim cast and mostly brown cast who are sort of living their own life, but also dealing with the sort of issues that I tend to write about in my novels. Both my books deal with quite very prominent ideas of race, class, identity, religion and things like that. I feel like as a person who is a visible Muslim, the advocacy that I do is almost so deeply ingrained in who I am, that it comes out in ways that I don’t even see as advocacy. And yet that is what it is.

HPA: And why is advocacy important to you?

UJ: Well, I think in again, coming back to my previous point, I don’t really see it as advocacy. I see it as living my life. And yet other people who are not used to people like me taking up space in their world, see it as me pushing back against the norms that they have always accepted and expected in their life. So when I write books that are centering brown Muslim characters and these brown Muslim characters, for instance, do not basically give up everything about their culture and their faith and completely subsumed themselves and sublimate themselves into the wider white context in which they live. That’s not me being an advocate.That’s just me writing a kind of perspective that most people have never seen before. And yet, to readers who are completely new to this, they might see it as like, “Oh, you’re advocating for your culture and your faith” And (I’m) like, no, I’m just writing about people’s lives that have traditionally been very much ignored on the page and screen.

HPA: But when you’re writing about these characters that are not traditionally found in these types of books, aside from being tokenized, it’s a side character, but you bring them right to the forefront. Even though you’re writing what you know and you’re not deliberately advocating, at the end of the day, it has a magic of advocacy to it because as a Muslim woman myself, when I’m reading your book for me, I’m like, “I’m so glad she wrote this book, because now other people can see who we are and how we live our lives, and that we are just like them”. So there isn’t that “othering” that is happening to us. So do you do you see where I’m coming from? Because I view that as even though you deliberately didn’t set on to doing it?

UJ: And I think that’s the magic of a representation, really, right? It’s like just by writing my truth, writing my own authentic lived experience, other people will benefit from it in all of these myriad ways. And you know, I get emails, DMs on Instagram and other social media from readers all the time, and they’re always a joy to read. It takes me a while to respond. Sometimes I do, sometimes I don’t (laughs). But I got this beautiful letter from an Arab Muslim woman in who’s living in France. And she’s probably fifth generation. She wears a hijab. She read my book, which unfortunately is not translated in French, so she read it in English, and she has never seen herself represented on the page like this. She was sharing some of the hardships and the extreme Islamophobia that she’s had to face, like removing her hijab every day before going into school, because that was an important part of our identity that was not accepted in the public school system there. And all of these other types of things. And it just gave me chills. I was thinking, I wrote this book sitting in my office a couple of years ago, and yet it’s somehow the magic of the spoken word, the magic of the printed word, has reached across an ocean and is touching this person’s life. She feels so connected to me in a way. And so I think the advocacy work that you’re referring to, it’s so important to reach out to others, but it’s also really important to reach within our own communities and let’s hold hands and realize that we’re going through very similar struggles. And one of the things that I try to do when I write is keep my audience in mind. I’m not writing necessarily for the white gaze, I’m not writing for my people. And I hope that it is a big tent, my people and trying to be as inclusive as possible. But I have a specific audience in mind.

HPA: Can you share with me and our audience why it’s so important for people to incorporate a sense of advocacy into their lives? It could be personal. It could be professional, it could be spiritual. Can you expand on that importance of bringing it into their own lives?

UJ: Because I think the world is unjust and it’s important that we as people stand up to injustice. You know, there’s an Islamic saying, “If you see something wrong, you should do something. You should try to change it with your hand, or you should try to change it with your tongue”. Meaning you speak out against it. And if you can’t do that because you don’t have the power or you’re not in the right headspace, “you should heed it in your heart”. And I always thought that was a beautiful Islamic Muslim Hadith, because it’s acknowledging the fact that sometimes you can do things to change, and other times all you can do is speak out against it, even if it doesn’t have as much impact. And other times you’re so powerless or you yourself are so weak for a variety of reasons that all you can do [is have] hatred in your heart. But at least you know what’s right and what’s wrong. And so I think advocacy can take on that that tinge you have to you have to figure it out for yourself. But closing your mind to the injustices that exist in the world, I think, makes you someone who’s not as compassionate and empathetic to other people. I never want to be that person. People always ask me, “Why are you still teaching high school?” I’m a public high school teacher in the in the GTA [Great Toronto Area] and it’s not just because I need to get out of the house or I’ll go crazy (laughs) but it’s also because I feel a real, tangible benefit to my job for society. I’m doing something that’s good for not just through writing books, but also through the act of teaching.

I realize that advocacy can take on so many different forms, even with the stories that I write. Simply by writing a book about Muslims with a mostly Muslim cast and mostly brown cast who are sort of livng their own life, but also dealing with the sort of issues that I tend to write about in my novels. Both my books deal with quite prominent ideas of race, class, identity, religion and things like that. I feel like as a person who is a visible Muslim, the advocacy that I do is almost do deeply ingrained in who I am, that it comes out in ways that I don’t even see as advocacy. And yet that is what it is.

HPA: So let’s talk about the of teaching, because we have to recognize that as well. How has advocacy been a part of your students’ lives? Are you seeing them understand and become more aware of it than before?

UJ: High school is a really weird time of life, right? And what I realized, both as a mother, I have I have two teenage boys at home with me. They’re amazing. I love them. And then I teach hundreds — I’ve taught hundreds of kids, maybe thousands of kids — I’ve been teaching for almost 20 years. And it depends. I know for myself, I think I was a late bloomer. I was someone who really sort of came into my own and thought about the world in my 20s. And some kids I see are very much — we have to remember, we have to acknowledge we’re coming out of a pandemic — so I do feel like the kids right now have experienced something that is shaking up adults let alone children. But some kids are very much consumed with themselves. So your typical kind of very self-absorbed just thinking about their own selves. But there are a lot of kids who have their eyes wide open to the world. And whether it’s through personal experience — I work in a community that’s very, very diverse, so most of my students are either immigrants themselves or they’re the children of immigrants — they know because they hear from home, stories about what’s happening in other countries. And so they have a very global perspective of the world. Some of them are activists already. Some of them are extremely well read. Others lie to me and never have read a book (laughs), they’re like, “Yeah, we like to read, you know, Instagram posts.” (laughs).

But we have to have space for all of these kids. Everyone’s on a journey. Everyone is different. And you know, the person that you are in grade 9 will be very different, hopefully, than the person that you are in Grade 12. And it’s so wonderful to me because sometimes I teach the same kids in grade 9 — like the batch that I’m teaching in Grade 12, I taught them in grade nine and now I’m teaching and half the class is like “Oh, Ms. Jalaluddin you taught us in [Grade 9] and now they are in Grade 12 and they’re different. In Grade 9, there was no COVID. I taught them in the first semester in September 2019 and we kind of spent some time together for five months. And now here we are in September 2021. And the world is a different place. They’ve changed. I’ve changed. Yeah, marking is never fun (laughs) because sometimes the kids were really challenging. But I always feel like the importance of education of an educator and the thing that I think I bring to the table, which is tied up in this idea of advocacy, is empathy and compassion. That’s what you have to bring to the classroom every day.

HPA: How have your students changed from the Pandemic?

UJ: There’s a sense of wariness, wary and leary. They’re tired of it. They’re cautious about the world. I think there’s a sense of trust that has been, shaken at an earlier age than it usually happens. They’ve seen systems fail them. Many of them have family in other countries, such as India, they have seen grandparents and aunts and uncles die or in China. And there’s also there’s a huge mental health crisis. Just across the board in society. I think people are talking about it a lot more. But we’re very worried for our students as well. And I can see that. I have a couple of kids, and just as someone who interacts with young people every day, this is something that you just keep an eye out to, just like, “okay, you need to talk to someone. Let me try to find you the resources”. We’re supposed to be another caring adult in their life. And, you know, I have big classes. I have 27 kids in my class, some of them are online, some of them are in, our in-person — teaching is crazy right now, but that’s sort of one of the roles that we can play while also delivering curriculum. Of course, I’m still a very strict teacher I have to say (laughs). That essay is still due (laughs).

HPA: Now talking about advocacy here in the last year specifically, so obviously with the pandemic, what have you seen that has stood out in how our world is changing to meet people where they’re at, rather than conditioning and fitting into preconceived ideologies?

UJ: I think this idea that we all have everything put together has just been cracked wide open. And, you know, we’re used to seeing the messiness of everyday life and we see this in so many ways, like, look we’re having this interview virtually. You can see into my office, right? And I kind of grab my bag of peanut butter cups keep in the corner and away from everybody (laughs). And then just that ability to see inside everyone’s houses and see how, you know, people have their kids crawling all over them or their cat’s kind of wandering through. There’s an intimacy there that simply wasn’t there before when we were all kind of well-dressed and presenting our perfect faces and now everyone is in each other’s homes all the time. So I think that has done something to help people. And also I think just the understanding of more [what the reality is] that people are facing at home.They call this the shecession. So we know that it’s impacted women, marginalized communities way more than it has others. We really see the difference. It’s like “OK, you’re a working woman. But have you been able to afford things like childcare or elder care? And now that those things have changed because of COVID protocols, what does your life now look like, and who’s taking on that burden of labour?” Sorry, I don’t know if I’m answering a question (laughs).

HPA: I get you. But now one thing which I do want to talk to you about is Slacktivism because Slacktivism has become a thing. For those who may not be familiar, Slacktivism is the notion that by creating or tweeting a hashtag, it’s also effective, giving the person the idea that they’re contributing to the cause by sharing the hashtag. In your view, what are the pros and cons of Slacktivism?

UJ: You know, this is such a great question. I remember reading it and thinking immediately of those black squares on Instagram, you know?

I don’t want to come across as judgmental, and I also don’t want to come across as not having expectations for myself and for others. I always look to myself first, and I think that outside of my writing, I don’t consider myself an activist, necessarily. I have a certain way that I view the world and that is shaped by my family, my culture. The privileges that I’ve been afforded. The fact that I live in a country where I can speak my actual opinion without fear of repercussions. I work in a very protected industry. I’m a unionized employee and and so I don’t want to come down too hard on people who might not see the world in the same way that I do. And even if they do, they share some of my same political viewpoints in the way that they express. That is, through things like changing your Instagram picture to a black square or to a green square or to whatever that is. I admire people who start those movements because I know some of them. I know someone who started the Green Square movement and we’ve all heard of the #MeToo movement. You know that particular hashtag or all the other hashtags that kind of have gained steam like #OscarsSoWhite. And there’s so many of them. #WeNeedDiverseBooks is something that, impacts me personally.

And ultimately, I think what Slacktivism does, it’s trying to harness the power of the many. And what that does is that it’s removing — and it’s the same thing that we were talking about earlier — the veneer that news has to be filtered and updates on what life is actually like on the ground for people has to be filtered through mainstream media, which is an extremely important part of life. Like myself, am I right? I’m a columnist for the Toronto Star, so I believe in the media, but that’s not the only way that people get their news. And we see what it’s like on the ground. For instance, when India was experiencing that COVID crisis, you’re still experiencing it. But we actually got live on the ground coverage. I’m saying India because my background is Indian, and I had family who were like posting updates on like “this is where you can find oxygen containers”, and it was just heartbreaking, absolutely horrifying to realize what my own cousins and my aunts and uncles are experiencing in India. It just was completely traumatic. And to get it from that point of view, as opposed to the filtered sort of CNN broadcast of what’s happening on the ground is completely different. So how I think that filters into this idea of Slacktivism is it’s a hashtag, yes, but some of these hashtags are really effective in causing change. And I think #MeToo was an example of that. So maybe this is just not [for] my demographic. Maybe I’m just too old for this. I’m not 20 or 50, but I remember as a 20 year-old going to protests downtown and just showing up, and I don’t do that anymore. Maybe those protests had absolutely no impact, certainly. Maybe it’s not a tangible impact. And yet the hashtag changing your Instagram, etc. etc., might be the only time that this person, whoever it is, a young person, an old person, medium-sized, medium-age person like me might be thinking about these really deep social justice issues. So I don’t know. I understand the criticism that it is, but it is based in posturing and it’s ineffective. The criticism that it is simply virtue signaling your base about how you feel about certain things. I get that, but I think ultimately I’m an optimist, and I hope that in some cases, it might lead to actual change.

HPA: Now my last my last question here is and obviously with your students too, and I think you’re kind of touched on this a little bit earlier with what you’ve seen and experienced, what advice would you give to everyone who’s watching, listening and reading this and who want to be more proactive in a cause that they believe in to actually get up and action it?

UJ: I would go back to the habits that I mentioned earlier, so that Islamic saying if you feel like there’s an injustice being done, try to change it with your hand, try to speak out against it with your tongue and if you can’t do that, heed it in your heart. And I think of it as a writer, that’s a classically written type of suggestion, because it’s in the climactic order. And I don’t think people realize that it is a climactic order. Climactic order means that it’s rising. But most people think if you change it with your hand, that’s the most important powerful thing. You change it with your tongue. That’s the second one. If you hate something in your heart, that’s the weakest of faith, and that’s how the Hadith goes. But I actually think that’s where it starts. You have to hate this injustice in your heart that you see nothing else really tangible will come out of it unless you really want change in your heart. And I would caution people to pace themselves as well because it’s really, really common for people to burn out when they do this kind of advocacy work.

HPA: Yeah, that’s so important.

UJ: It’s a huge problem. And you see that one or two people are — it seems — they’re taking on the burden of the world. And you can’t do that. You won’t last — maybe [for] a couple of years. And then you’ll be so burned out you won’t be able to do anything.

But changing the world is a life-long process. Nothing is going to change overnight. I work in a huge bureaucracy. You know, any school board, it’s like the school board I work for is the largest employer where I live and changing a huge machine like that, changing a government, changing even within a corporate structure, it takes time. And I think sometimes as young people, they want to advocate for change right away, which I love. I love that they want that because you need the young people to rattle the cages, but you want to make sure that you stay there and you keep rattling those cages and with the understanding that it’ll take time. But things have the potential to change now. I mean the Climate Change Conference in Glasgow [is happening now]. And it’s so hard for me to not be cynical about it because we’ve all seen this before. This is not our first go around on this merry go round. “Oh, the planet is burning”. “We’re all in crisis”, OK? But we’ll change it by 2050, “2050? What the heck?” you know? I think you have to temper your need to change things immediately. With the acknowledgment that the world must move slowly is actually an important part of change to go slow. Because that’s when you have the most thoughtful change that happens and[it’s] slow. Slow doesn’t mean that we’re going to wait 30 years for something, maybe a year or two. You know, and I just think about the way that social attitudes have changed about so many things. For instance, the LGBTQ movement has made leaps and strides in the way that we talk about that community and the way that we become so much more accepting of that community. And that’s that’s one example. I think that has come a long way. It’s just great.

Young people, they want to advocate for change right way, which I love. I love that they want that because you need the young to rattle the cages, but you want to make sure that you stay there and you keep rattling those cages and with the understanding that it’ll take time.

HPA: Wonderful. And our time is coming to a close. Thank you so much. It was my thank you for sharing your perspective with our global audience. And congratulations again on being part of The ANOKHI Advocate list. Thank you.

UJ: Thank you so much.